Hey! Let's talk about #SSH and #security!

If you've ever looked at SSH server logs you know what I'm about to say: Any SSH server connected to the public Internet is getting bombarded by constant attempts to log in. Not just a few of them. A *lot* of them. Sometimes even dozens per second. And this problem is not going away; it is, in fact, getting worse. And attackers' behavior is changing.

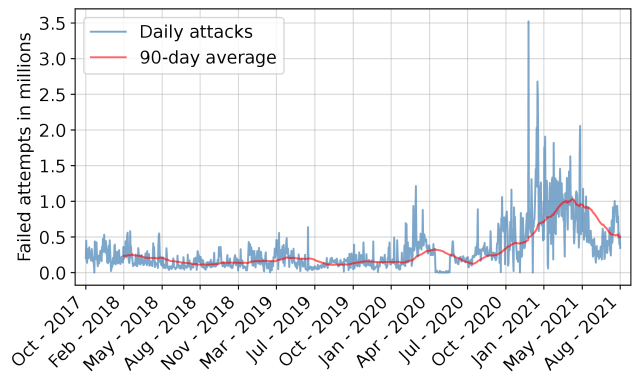

The graph attached to this post shows the number of attempted SSH logins per day to one of @cloudlab s clusters over a four-year period. It peaks at about 3.4 million login attempts per day.

This is part of a study we did on our production system, using logs of more than 640 million login attempts, covering more than 1,500 hosts on our side and observing more than 840 thousand incoming IP addresses.

A paper presenting our analysis and a new, highly effective means to block SSH brute force attacks ("Where The Wild Things Are: Brute-Force SSH Attacks In The Wild And How To Stop Them") will be presented next week at #NSDI24 by @sachindhke . The full paper is at flux.utah.edu/paper/singh-nsdi…

Let's dive in. 🧵

some fedifriend

in reply to Rob Ricci • • •I've got a big picture question that may sound silly: What's the point in blocking the attacks?

If you've got user accounts with weak passwords, then that is a problem that should probably be addressed with higher priority than the frequency of attacks.

If you've only got users with strong public keys, then attacks won't succeed anyway. Blocking them will save you some resources, but will also redirect the attackers to weaker targets. Isn't it overall better to just tank the attacks?

Rob Ricci

in reply to some fedifriend • • •@samgai Not a silly question at all, it's a great question!

One reason to block ssh brute force attempts is that you may have devices on your network that you don't know are vulnerable: for example, we see lots of attempts to attack IoT devices, such as a big spike of attempts to log in to accounts associated with the Dauha backdoors when those were revealed. We also see lots fo attempts to log into routers from various vendors (Unifi, MikroTik, and Huawei).

Another is that in some cases, you don't have full control over your users. The facility we operate is cloud-like in the sense that we do control the initial configurations of sshd and can force users to use good passwords, but after that, they have root and can - and do - change configurations or set local passwords in a way that makes the vulnerable.

A third reason is that a lot of these attacks are *probably* coming from botnets that are launching a range of different kinds of attacks. So if you can easily recognize them as ssh attackers, you can block them completely, possibly saving yourself from other attacks.

Finally, they consume resources on the target machine - maybe not a lot, but heavy attacks can have a significant impact, and we want to keep this impact low.